What is an Interval in Music Theory ?

Image courtesy of Vidar Norli-Mathison

Image courtesy of Vidar Norli-Mathison

What's an interval ?

An interval can be described as either a gap, or a relationship between two pitches. While a single pitch, or note is nice, in order to make complex and interesting music, we need to understand how any two pitches will combine. Knowing about intervals will tell us if the sound they produce will be good or bad, happy or sad.

What's the Difference Between a Pitch and Interval ?

The difference between a pitch and an interval is that a pitch is a measurement of just one frequency. It is fixed, unambiguous. An interval is a relationship between two pitches and it's qualities are open to interpretation.

This next sentence is technical - read it twice or thrice if necessary. It helps if you imagine plucking a piece of string.

All sounds have pitch and pitch is a numerical measurement of the resonating frequency and is expressed in Hertz. The higher the pitch, the higher the number. Pitch is purely a technical measurement which is not subjective and can be measured with a machine. For example, standard concert pitch for middle 'C' on a piano is 261 hertz.

The 'C' above middle 'C' is double 261.6 hertz, ie 523.2 hertz and each 'C' note shares this relationship of being either double or half it's nearest buddies frequency. This is true for all the other notes too. So if 'A' is 440 hertz, the next highest 'A' will be '880' hertz.

It just so happens that if you get your piece of string and pluck it. Then you half the length of the string, then pluck it again, the pitch frequency will be double what it was before you halved it.

Intervals are much more about how we hear sounds than measuring them.

So What's an Interval Again ?

An interval is a difference in pitch between two pitches ( or notes ) like those above. But they're not expressed in hertz, they're are measured on a degree of scale of 1 to 8 ( 1st - 2nd - 3rd etc ) and are used to help us understand the strength of harmonic relationship between the two notes.

To go back to the piece of string, there is a very strong harmonic relationship between the full length piece of string and the halved version of itself. It's these relationships, these intervals which help us make good music.

But we don't just want to know about halves and wholes. We want to be able to make our string lots of different lengths, don't we ? After all, that's how we get lots of different notes. We usually divide our string into eight lengths.

Why Are There Eight Notes ?

There are eight notes and degrees of scale because in the western music tradition, between any two 'C's there are eight notes which are the most useful, so we use those eight the most. That's it !

Only kidding, it's way more complicated than that. But the eight notes of the major scale is our starting point.

What's Great About Intervals ?

Intervals are great because any two notes which are sounding at the same time produce a harmonic interaction in our ears which we find pleasing. The trouble is that some pairs of notes are not so pleasing and some pairings sound pretty horrible.

If we know that an interval between two notes is, for example a '5th,' we can predict with some accuracy that the sound produced will be pleasing.

On the other hand, if the interval between two notes is for example a '2nd,' we can predict that the sound will not be pleasing, and many folks would call it horrible.

Music theory being what it is, the quality of harmonic relationship between any two notes does not become better or higher if the number is higher, that would be too easy. For example, a '7th' is not a better interval relationship than a '5th.' But a '3rd' is a better interval relationship than a '2nd.'

It's important to realise that there is an element of subjectivity involved because everybody interprets harmony between notes at a personal level. But below there's a chart with a guide to the relative strength and qualities of intervals.

Musicians use terms like 'consonant' and 'dissonant' to split intervals into two camps. It really means how stable and unambiguous the interval sounds. If it's described as 'dissonant,' it's unstable and sounds like it needs to go somewhere. This distinction is a bit simplistic because intervals often fall in between the two camps.

The key thing to remember is that if the relationship is 'consonant,' the sound produced will be nicer than if it is 'dissonant'

| Interval Names and How They Sound | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Half / Semi-Tone Gap | Various Names | Consanant / Dissonant | What it Sounds Like |

| 0 | Unison | Consonant | Good, settled, resolved, same note, same pitch, difficult to tell two notes apart, a bit boring. |

| 1 | Minor 2nd, diminished 2nd | Dissonant, not used in the major scale | Really ugly, bad, unstable, scrappy, but useful for creating tension. |

| 2 | 2nd | Dissonant, but used in the major scale | Ugly,unstable, not nice, not great. |

| 3 | Minor 3rd | Consanant, used to define a minor scale | Good, resolved, stable, but a little sad. |

| 4 | Major 3rd | Consanant, defines a major scale | Happy, resolved, stable, nice and good. |

| 5 | 4th, perfect fourth | Consanant/dissonant, used in major scale | Nearly good, but a little unstable. |

| 6 | Augmented 4th, diminished 5th, flattened 5th, tritone, devils chord | Dissonant, not in the major scale | As bad and ugly as it gets, used to represent danger, evil or total ambivelance, so has many uses. |

| 7 | 5th, perfect 5th | Consonant, strongest interval of any scale | As good as it gets, stable, happy, very nice. |

| 8 | Minor 6th, flattened 6th | Consonant/dissonant not used in the major scale | Slightly unstable, nice-ish, but murky when played low |

| 9 | Major 6th, perfect 6th | Consonant/Dissonant, used in major scale | Just about stable, not ugly, not sad, almost good |

| 10 | Minor 7th, diminished 7th | Dissonant/consonant not used in major scale but oddly attractive. | Unstable, not nice, not sad, but interesting like it's asking a question |

| 11 | Major 7th, perfect 7th | Dissonant, but used in the major scale | Unstable, not nice, not sad, very similar to minor 7th like it's asking a question, but more urgently. |

| 12 | 8th, octave | Consanant, last note of major scale | Good, happy, very nice, same note as starting note, different pitch |

What's the Difference Between Notes and Intervals ?

Notes may be compared with pitches in that they describe one sound, whereas an interval is a relationship between two sounds. ie two notes or between two pitches.

A note is different than a pitch because within the spectrum of human hearing there are many 'C' notes. But each of those 'C' notes will have a unique pitch frequency so we end up calling them 'C1' 'C2' 'C3' etc. The interval between all the 'C's everywhere in world are multiples the 8th ( the octave ).

What's the Difference Between a Chord and an Interval ?

A chord can be any collection of notes from two upwards. A two note chord would comprise one interval. Three notes would have two intervals; one big interval and two smaller ones. You could say that a nice chord is a collection of well thought out intervals. Equally, a bad sounding chord is a bunch of poorly chosen intervals ( unless you chose them especially to make an evil sound ).

The important thing is that without an understanding of which intervals to use in the chord, the chord would not sound good or beautiful. To most people, it would just sound like noise.

What's the Difference Between a Scale and an Interval ?

The notes of a scale are the pitches which are sounding. The intervals are the gaps between any two notes. The gaps between the notes is what defines the scale and makes it sound different from another scale.

There are lots of different scales and modes in western music. They nearly all have eight notes and seven intervals.

They all start and finish on the same note, for example 'A B C D E F G A.'

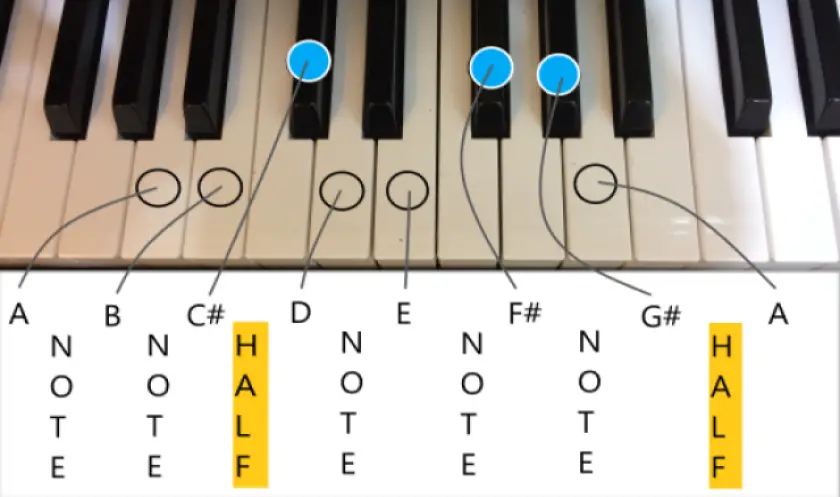

If you're playing a major scale, it doesn't matter which note you start on, if you stick to the pattern of intervals which goes , NOTE - NOTE - NOTE - HALF- NOTE - NOTE - HALF - NOTE. You will always get a major scale.

Intervals in a scale of A major

Intervals in a scale of A major

This is really important because, knowing this pattern, you can now start with any note and be 100% confident you'll get the same type of emotion in your music.

Why Are Intervals Important ?

Intervals are unquestionably the single most important aspect of music theory because intervals define and explain how scales, chords, harmonies and melodies are built.

If we didn't have something called an 'interval' we'd just have 'nice' noises and 'not-nice' noise so you can bet we'd end up calling the gap between frequencies something or other. Like 'gaps' for instance.

If you want to be silly about it, you might call an interval 'a 261 megahertz gap.' I don't think it will catch on and anyway, it wouldn't work because no two 'C' notes have the same megahertz gap.

Why Are Intervals Hard to Understand ?

Warning : this paragraph is a stupidly condensed version of the most confusing and misunderstood part of music theory - if you get to the end of it without having a meltdown - then you've got what it takes to be a musician.

Intervals would be easy to understand if they were simply numbered from 1 to 12. That way, each semitone/ half-tone, could have a number.

That's never going to happen because music theory encourages us to understand any group of 12 semitones as an octave. YES that's really confusing. It encourages us to concentrate on just the 8 of the 12 tones which form a Major scale with the other 4 tones ignored as unused spare tones. But remember, you can't ignore those 4 tones completely because they're always needed for something.

So, even though it's much easier, we're discouraged from counting intervals as 1 to 12. Instead we count intervals as 1 to 8. And all the spare tones, that is all the ignored tones, are called 'diminished' or 'augmented.'

There are conventions for deciding whether to call a tone diminished or augmented. Sometimes they make sense, sometimes not.

You can say that a '3rd' is diminished, and it often is. This makes sense because instead of playing a note we might call 'E', we play the 'E flat.'

So the diminished version of 'E' is a semitone lower in pitch.

But you wouldn't say ' hey Paul, play an augmented E' because a semitone higher than 'E' is not 'E shape' but 'F'.

This is just one example and don't spend too much time on it. Just know that it exists and there are others which you'll take great pleasure in discovering. '

How do I use Intervals ?

Once you understand the quality of harmony that a particular interval produces, you'll be able to use it to invoke emotions in your audience. You'll soon realise that there are good, bad, happy and sad intervals. There are also settled and unsettled intervals. You can use this knowledge to create a sense of tension and release in your music. That's a very potent combination.

All through this article, I've talked about an interval between two pitches. Most music uses chords which have 3 or 4 or many more notes. Each interval will change the nature of the sound as the they are built one on top of the other.

You use intervals more and more as your musicianship improves, until eventually, you start to see music as intervals rather than notes. You'll start to invite certain reactions from your audience without using words at all, cos the emotion will all be in the intervals in your music and people will get it instantly without the need for words.

You can't have music without intervals. Every melody, chord or scale you play is totally dependant on your understanding of intervals.

If you get in to the jazz genre, you'll find some intervals are treated quite differently than in most other styles, some are avoided at all cost. But if you understand intervals - you'll understand music.

Conclusion

An interval is a gap or distance or relationship between any two pitches.

Some intervals sound good, some sound bad, and some sound ugly. It often comes down to our interpretation of differently pitched noises and what other intervals are sounding or have just sounded.

Although music theory tries to make generalisations about intervals, our judgement and appreciation of intervals is usually personal and subjective.

Intervals are the most important and useful part of music theory. They are everywhere and you can't have music without them.