25 Special Songwriting Secrets : And Why Each One Matters

Image courtesy of Nathan Bingle

Image courtesy of Nathan Bingle

Like cake, good songs need a few special ingredients, otherwise they turn out a bit flat and boring. And it's just as important to know if you've overdone the fairy dust, as it is to know when something's missing. Now, some of these ingredients are not all that secret, but all are a bit special and often overlooked and misunderstood.

Sadly, a song is more complex than cake, it has many moving parts which must work together like a synchronised machine. It must organise totally random noises into a sequence which imitates the emotions of the human mind.

And your music has so much more to do. It must conform to certain social or cultural expectations whilst being a magnet for our deepest hopes and fears. It must be an entertainer, a healer and safe place to be. It must be gentle enough to soften the hardest heart and powerful enough to encourage people to take up arms. In short it's almost like casting a magic spell – so let's look at the stuff that goes into one and see if we can make sense of it.

1. The writer's mind : Essential

Image courtesy of Sanket Kumar

Image courtesy of Sanket Kumar

It's imperative to be in the right frame of mind when trying to be creative. This gets easier the more you do it. For example, if you write every day, you have fewer days when you're unable to produce anything and you develop your own routine for getting into the zone. The things is, When it comes down to it, a song is a reflection of the writer's mind, and the trouble with that is, the poor old human mind is often in conflict with itself. It's constantly weighing up options trying to figure out the best course of action without knowing all the facts. Remember, it's stuck in a box with no real access to the outside world so it's at a considerable disadvantage. It's no wonder that so many songs are written which appear to make no sense. That said, any mind, young or old, is quite capable of sorting all the confusion into a stream of musical bliss.

We all know what a song should sound like like. We only need listen to our favourite artist and let the ebb and flow sink into our souls. The next step is to start asking the right questions about the music you're listening to. How could I recreate that rhythm ? Why does this line always make me want to dance ( or cry ) ? How do I invoke that emotion ? Why does the refrain happen here ? How is this bit quieter ?

I'm not suggesting you copy. I'm suggesting you use what you know as a reference to help you learn how the song was built. Once you immerse yourself into another's work by taking it apart, You will begin to see what it's made of and how it does what it does to affect you. This is an important distinction. You need to get your head out of the shed of the listener and into the studio of the artist. This is all part of getting into the creative zone, having your mind fuelled up and tickled with curiosity, then song writing will be much easier.

It will be easier still if you truly believe you can finish the thing. It's been my experience that doing anything new always takes longer, is harder and much more complicated than first envisaged. When you get stuck you need to develop the tenacity to keep trying new approaches. Believing you'll be successful is the biggest hurdle and the single most important element you need for writing a song.

2. The Listener's mind : Important

If a song is written with the intention of being sung for an audience then it must engage them. Without them the song is just a form of self therapy. Not until it is released into the world will it really come to life and begin influence people.

And luring people into your imaginary world is a delicate balancing act only achieved by the most emotionally intelligent crafting. The trick is not to tell the audience absolutely everything that ever happened. Quite the opposite. Let them bring their own experience and interpretation, that way they are far more engaged because your story is now also their story.

Leaving something to imagination is one thing, being ambiguous another. The perfect balance is somewhere between; but if in doubt – leave it out.

The importance of allowing the audience space to digest you music is a fairly advanced technique and won't always be appropriate. That'll be between you and your audience. But one of the magical moments in music, as any performer will tell you, is that instant when the audience buys into your story. It's an unseen, subtle sensation, but it's very real indeed, and can often be noticed by the quality of the silence.

Don't forget, listeners enjoy falling under the spell of a song; especially when it resonates with their own experience or because the presentation is such that they can easily empathize with the issues being portrayed. There's a kind of transmogrification, an exchange of ideas which takes place in the room and in their minds. They're suddenly reminded of something they'd forgotten. The colour of their mother's hair, a lost lover's smile, the feeling of meeting someone special. Without your song, their memories, which may be very deeply hidden, would not be aired. So remember, the song is not only about the singer, it's just as much about the listener.

3. Story : Optional

A dance song need have no story because the rhythm is going to trump or out compete the words and their meaning. This might also be true in any upbeat song from any genre. Certain pop songs are famous for their nonsense lyrics and even well known established writers will cobble together a lyric based on unconnected words which just sound right.

Opera in a foreign language can reduce grown men to tears even though they have no idea what is been sung. That said, in most cases a song that has an unfolding story with several perspectives usually has more appeal. Our brains like stories and we're far more likely to engage with someone telling a story than someone shouting 'I'm unhappy, I'm unhappy.' OR 'hey fur zook an diddle eye day'

Traditionally, and I mean, going back before we had pen and paper, song was used as a means for people to remember their stories and share them with the next generation. Wars, famine and scandal were all remembered and passed on to give a culture a sense of who they were.

4. Words : Important

Words have a lot more clout than story. Especially if you have no story. Their phonetic nature has a musical mini rhythm unique to each word and so in any event, you should always use the best sounding word you can. Not necessarily the most accurate but the most phonetically poignant and musical. Some words are simply not nice to sing and some don't compare or contrast with the words around them.

Words have a lot more clout than story. Especially if you have no story. Their phonetic nature has a musical mini rhythm unique to each word and so in any event, you should always use the best sounding word you can. Not necessarily the most accurate but the most phonetically poignant and musical. Some words are simply not nice to sing and some don't compare or contrast with the words around them.

A dictionary, and thesaurus are invaluable tools and you should always have them to hand when writing. You will almost certainly get stuck because you can't find the right word. You will also keep mulling over phrases because you sense a word is not quite right. It may take a weeks or even months because you keep changing your mind about something, that's normal.

It's best to mix words of differing lengths if you can because the odd long word can be very handy here and there to make a point, at the end of a phrase for example. It's also a good idea to use action verbs where ever possible because these imply something is happening when it isn't. For example, instead of, 'the lovers were in ecstasy,' how about, 'the lovers lay in ecstasy' or 'lovers,,,,,,, writhing in ecstasy.

Another simple way to give your words impact and trip off the tongue nicely is to use alliteration.. This is a type of rhyme where the words begin with the same letter. For example, 'the unruly Orang Utan was unusually unhappy with his umbrella. ( Which is OK if you like 'U's ). In song and poetry it's perfectly acceptable and smugly rewarding to use made up words such as 'terrifrightened' or 'splenditious.'

lastly, there are many types of rhyme but remember, it doesn't matter how loud or strong your words, their meaning will always be overshadowed by what's happening in the music.

5. Rhyme : Important

A lyric with no rhyme can usually be more believable than one without. There is an honesty which is lacking if the ends of phrases are engineered towards the rhyme. Going further, it's important not serve the rhyme in favour of the meaning or you'll sound very cheesy, clichéd and forced. But millions of songs and poems use rhyme and it's not that common in popular music to find pieces which have no rhyme at all.

The human mind is very good at spotting rhyme and you only need a hint of it to be effective. There are many rhyme types for instance a semiryhme will have an extra syllable as in, 'hall – hauling.' An oblique rhyme will require a stretch of imagination at first as in 'Graham's crayon.' A pararhyme will have matching consonants as in 'ball bale.' You can rhyme anywhere you like and and as tenuously as you like. Once you get hooked by it, rhyming can become quite addictive an fun.

A really clever way to use rhyme is to offset them by pulling the timing slightly out of line with expectations. For example: 'the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog, but the hound on the ground has frog in his throat.' You may feel like the 'og' sound should be at the end of the phrase, but you'll find it limits your options for the next line and also, your listener may have already anticipated that particular rhyme and become bored and uninterested.

An invaluable tool for rhyming is a rhyming dictionary, it will solve many a rhyming dilemma and give you ideas which point in interesting new directions.

6. Repetition : Important

Repetition is every where in music. The rhythm is a repetition, the melody is almost always repeated. The form and chord structure is almost always repeated. Words are repeated and if you think about it, even a rhyme is a form of repetition. Listeners expect repetition so don't shy away from it, but don't go overboard. As a rule of thumb you should mix it up. Give your listener something they know, then something they don't.

Repetition is important because it lulls the listener into a state of mind. It helps them forget the business of daily life and brings their attention to one place, this place, this safe place where things that we don't understand can be explored.

Repetition also the easiest, often laziest form of song writing. If you get stuck just repeat until something wants to take the place of the repetition.

7. Melody : Essential

Melody is a key element and is something you don't want to get wrong. When you're composing, you don't want a melody line which jumps all over the place. It needs to be easy on ear and reflect the mood of the song. Mostly, don't stray to far away from the last note. Move gradually in waves, building a little higher for anger or happiness and lower for sadness and gravity. When there's a need to emphasize a key change such as at the chorus, it can make larger jumps to emphasize change and create impact impact.

You can sometimes get a hint of how the melody could go by listening to how the lyrics rise and fall when spoken. It may surprise you to know that there's often more melody in the spoken word than in a song. How many times have you heard the statement, 'it's not what they said, it's how they said it ?' Well, that's an example of the magic of musical expression. It always, always serves to overpower the normal meaning of words because a pitch change is more primal than language and its symbolism is understood even in very young infants.

You don't have to know someone that well before you can exchange simple gestures with umms, arrs and few well placed grunts. Chimps are quite capable of making themselves understood quite well without words, especially when there's food about.

It is quite possible to write a song melody which never changes pitch. Mediaeval plainsong was sung in churches all over Europe and it often has a chant which only changes pitch at the last syllable. Staying on one note is extremely effective because it builds tension. Even though the pitch hardly changes it's still called the melody line, that's the part it's referred to in the music.

Bad melodies are deal breakers, luckily we have an inbuilt sense of what's roughly right or wrong so it's unlikely a person writing for their own language and culture will produce garbage. You just have to trust your gut.

A melody doesn't have to be complicated or agonized over. If you keep repeating your lyrics to yourself, over and over, they'll tell you what's working and what isn't. Usually, the answer's there in front of you if you just let it happen.

8. Rhythm : Essential

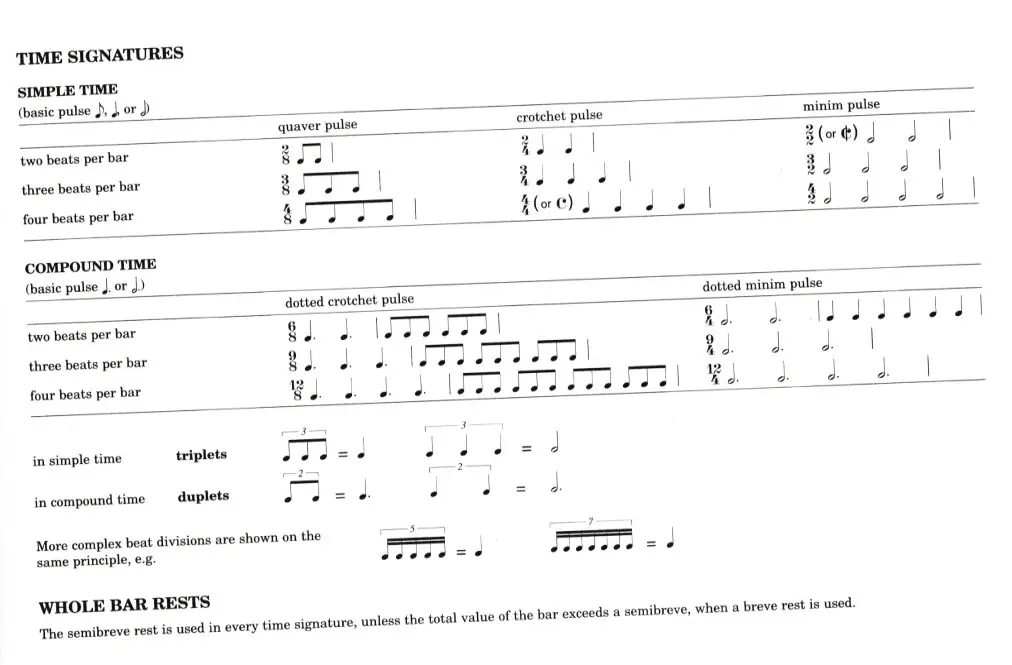

Rhythm is the one thing a song can't do without. It is pretty much what separates singing from talking. When we sing, we adhere to a fixed rhythm. We may extend certain vowel sounds to emphasize them but they always fit the time signature ( hopefully ).

Rhythm is the one thing a song can't do without. It is pretty much what separates singing from talking. When we sing, we adhere to a fixed rhythm. We may extend certain vowel sounds to emphasize them but they always fit the time signature ( hopefully ).

By contrast, when talking were constantly speeding up and slowing down. We pause in unusual places and restart unexpectedly. That's quite difficult to do with song – and difficult to listen to. We expect our songs to behave in a certain way and having a fixed rhythm is top of the list. When you begin to write a song, the first stating point should be the rhythm. Especially if it's a dance track or any other instance where the words must fit the music precisely.

Time signatures look like fractions and come in manner of confusing combinations. These are just a few and you could make up any rhythm you like. But this is getting into music theory and beyond the scope of this article. Unless you're writing a score for other musicians you're unlikely to need to write it down. Rhythm is something we all feel, we all have heart beats, so we all understand it, honest we do !

9. Tempo : Important

Tempo is the speed of the rhythm. It might get faster especially towards the end but it's usually same all the way through and is marked in beats per minute, ♪ = 60 for example. Whilst writing a song, you wouldn't worry about it to much until you have your lyrics and other parts pencilled in. A ball park figure is usually good enough.

What's important about tempo is that you listen to a recording of it before you play it to somebody – you'll find it will probably be a bit on the slow side.

10. Volume or Dynamic : Optional

When I say optional, I mean changes in volume. Obviously you have to be loud enough to be heard but varying the amount of noise you're making is great way to emphasize a passage such as a chorus. Composers have used this tactic for centuries and today many bands make 'loud versus a soft' a feature of their sound. This is where we get the term 'pianoforte' from. Piano being soft and forte loud. You'll probably do this without even noticing because as we sing higher, we tend to get louder. Unfortunately, even the most educated musical mind is pretty dumb when it comes to volume. As far as the brain is concerned Louder = Better. That's just the way it is.

Interestingly, certain types of sound don't have to be loud to be heard by the human ear. Take the rasping buzz of a chainsaw, distorted electric guitar or Hurdy-Gurdy. Do they remind you of anything ? Like it or not, they do. Our brains are pre-programmed to react to the sound of a crying baby. So these sounds and others which have that particular sound will be heard through a cacophony of other sounds and interpreted automatically a distress call. More music magic !

11. Harmony : can be Optional, Important, Essential

You have lots of choice with harmony. Your song will survive quite happily without any harmony at all or you can make the whole piece an exercise in harmony. It's a term given to any collection of notes which accompany the melody and add another dimension to it. If you play a piano or guitar, your instrument should be in harmony with your singing. Harmony is one of those elements which can overrule your nice cheerful sounding words and make them sound depressing. It can also do the exact opposite.

In western music the most common example of harmony's power would be the difference between major and minor chords. Although, some people don't perceive minor chords as 'sad.' And in the Baroque period minor keys were not only used for ballads, so this 'sad' label is probably more a modern convention than fundamental symbol of expression. But it's important.

Strictly speaking, you only need two notes for a harmony and how harmonic they are depends on their wave length in the relation to the melodic note. Basically, if the wave forms don't interact well they hit your ear drum unevenly and your ear won't like it. And guess what, not all ear drums are the same so different individuals have differing preferences for dis-harmony.

In music theory, there is a fairly well accepted hierarchy of 'nice' through to 'ok' and 'not nice.' Nice is usually interpreted by our brains as happy, sorted, stable, resolved. As you move further away into dis-harmony or dis-chord, it becomes unstable, uncomfortable and unresolved. So you may already have guessed that unharmonious harmony is the number one tool for creating tension. In this respect, you could argue that harmony is essential.

12. Instrumentation : Optional

Choice of instruments tends to be dictated by genre, especially in more popular music and they all come with their own social preconceptions or baggage. The tonality of the instrument will have something to do with this but again it's all mixed up with social expectations and practicality.

Choice of instruments tends to be dictated by genre, especially in more popular music and they all come with their own social preconceptions or baggage. The tonality of the instrument will have something to do with this but again it's all mixed up with social expectations and practicality.

Nothing can match the depth and range of emotion expressed by a sixty piece orchestra. But moving one around requires several coaches and a lot of organisation. A piano is a superb polyphonic instrument with great harmonising capabilities, but lugging a keyboard around is flipping hard work. Guitar is much easier, though limited and ukulele even more so. And banjos, well, aren't they just for country songs ? Mmm, not sure.

The more instruments you have the bigger, richer, more flexible and more interesting your music becomes. You'll have a hard time entertaining people with a ukulele for a whole evening. But every instrument you add makes things more complicated. They often get in each other's way so you can't have everything playing at the same time or you just create a horrible noise.

Just remember that in song, all instruments are harmonisers and so should always be supporting to the vocalist. They should not be too busy or too loud or too many, otherwise they risk overpowering the singer. When the singer is singing, they should be quiet and boring.

13. Genre : Important

Genre is a tricky subject. Consumers and promoters of music love to label music but musicians often hate to be type cast. When describing music, we nearly always have to compare it to something known to give people a reference. If you're writing for an audience such as film and TV licensing where genre is everything then, genre is everything. If you're writing for a competition it may be irrelevant, but you may still have to write some text describing it. If you become known as a blues artist, you will likely lose many fans if you decide to change your style toward jazz. You see, people like genres, even when they say they don't.

When you're starting out, you'll most likely be influenced by the artists you respect and consequently you'll probably sound like them. This no bad thing because it gives you a template and gets things moving. So long as you know that you're going to be type cast you can adjust accordingly. There's no getting away from genre, even though you may want to.

If you do really want to, your best bet is to mix two genres together or if you're really clever create a new one. Lots of people have. Enya, Elvis, Brian Eno, and that's just those who's names begin with a letter 'E'.

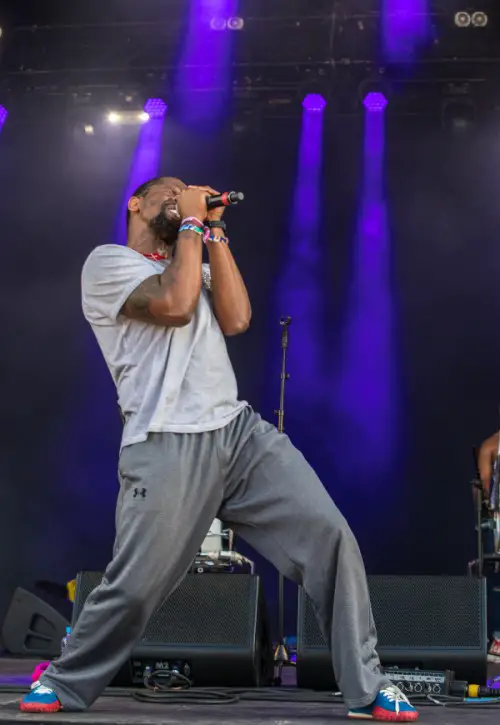

14. Performance : Essential

Image courtesy of Slim Emcee

Image courtesy of Slim Emcee

Absolutely essential. Performance is the difference between being heard and being understood; between communicating and connecting. When you put your ideas into the air, your listener won't believe your heart is breaking if you sound like you're already getting over it.

If your heart is breaking then it must be breaking right here and now in front of this audience and it must hurt so bad that they either feel compassion for your plight or are reminded of how their heart is broken too. Same with happy songs. You can't get people to believe you and come into your imaginary world if you look or sound miserable.

Expressing the emotions in the song is not enough. You must live the emotions and what's more, demonstrate your vulnerability to them. A certain amount of acting and falsehood is inevitable, after all, you can't actually relive the intensity of those emotions at the drop of a hat. But unfortunately you must try to get as close as possible, and for every performance.

There are considerable advantages in this approach. Firstly, it makes it easier and more interesting for you as a performer and secondly, living in the emotion of a piece helps reduce or even eliminate stage fright.

15. Crescendo : can be Optional, Important, Essential

Not all songs are roller coaster journeys into the highs and lows of emotion. A dance track may just keep that beat going nice and steady. A sacred church song may exude steadfast, unyielding devotion without any change in emphasis. Children's songs, especially if they are based on a nursery rhyme, will not usually be over dramatic as young kids tend to sing loud all the way through with little change of expression.

Some songs, however, will appear flat and unfinished if there is no high point. A ballad or aria is a prime example. There needs to a point where the singer, just can't take it any more. They must reveal their total vulnerability, and break down into a smouldering heap.

This usually happens around three quarters of the way through. Very often in a section called 'the bridge.' It may have a key change or modulation or some other noticeable shift in perspective. It will be the point the song has been building towards and if done correctly, will be the part most listeners start to cry. It may include extra or new instruments and will usually be louder. In a ballad, it may be more effective if done quietly, to make it intimate and personal.

If you're writing a triumphant or celebration type song, then you'd have to make it louder, higher in pitch and have all or most of your instruments playing. Thereby turning it into real tub thumping 'party on' frenzy. Your crescendo could be the hook for entire song.

16. Structure/Form : Important

For some people structure is essential and it's true that every song needs a beginning middle and end. Even if it's a simple chant with no high and low points; the writer is better equipped with a structure in mind. Otherwise, the song could drift into an obscure rant. For a listener, the piece might then appear boringly long and intolerable.

It is usually much easier to write if you've mapped out which bits are going where such as in the one below. There are oodles of structures and there is no correct one. However, it's worth knowing that certain structures tend to be expected. The classic 60's 70's 80's pop songs would go, verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, instrumental, chorus. You won't go too far wrong with this structure – but remember, everyone else is doing it too.

Some people can't write to a structure. They find it too constraining and like rhyme, having it in the back of the mind forces their attention away from artistry and into serving something which dulls creativity. If you feel this way then you're not alone, don't worry about it. Write your song how it needs to be written. Once you've said all you need to say then you'll find the structure will probably look after itself.

17. Hooks : can be Optional, Important, Essential

It's wise not to get too hung up on hooks. If you spend all your creative energy writing small, unconnected hooks, your songs will be very shallow, lack conviction and have limited appeal. But if you think about the whole song being one big hook or series of variations, then you'll be onto something. This approach goes back a long, long way. Beethoven used it and he seemed to do all right by it.

It's wise not to get too hung up on hooks. If you spend all your creative energy writing small, unconnected hooks, your songs will be very shallow, lack conviction and have limited appeal. But if you think about the whole song being one big hook or series of variations, then you'll be onto something. This approach goes back a long, long way. Beethoven used it and he seemed to do all right by it.

A hook can be a particular lyric or tune or rhythm or sound or set of sounds, pretty much anything which is catchy or emotionally powerful enough to stick in a listener's mind. It could be a short refrain, a whole chorus or a tribal chant which invites the listener to sing or shout along.

The type Beethoven used were musical motifs repeated in various guises. In his famous 5th symphony the rhythm also play a significant role as hook. At the time people didn't know what to make of his music because they hadn't heard anything like it before and therein lies a secret.

Your hooks need to be original or unusual or unexpected. Such as a sudden change in loudness, rhythm or direction. Even a well known, overused cliché can make a good hook if it's presented in an unexpected context. Take a moment to think what you could do with an everyday phrases like, 'here is the news' or 'wish I had a boyfriend' or 'Johnnie lost his way again?' This is great way to start a song because the phrase becomes the title, the hook and the metaphor for your whole story. Metaphors make good hooks and very powerful songs indeed.

18. Metaphor : Optional

This is a rather advanced technique because metaphors can be a bit tricky. A metaphor is usually anything which represents or symbolises another thing. For example, 'snow on the mountains' is symbolic of winter. 'Falling leaves' are symbolic of the end of summer but they could also symbolize the end of anything you want them to.

At the time of writing, Lizzo's 'Good as Hell' keeps popping up. Her lyrics 'I do my hair toss, check my nails,' is catchy as hell. For me it's about the attitude of woman with a healthy mind set. She's saying she's going to have a positive approach to whatever lies in font of her; she's going to be confident and be seen to be confident. After all, a woman who does these things has her head screwed on, right ? These actions, these symbols, remind her that confidence on the outside means confidence on the inside. They become metaphors for confidence.

But in a song, the symbol can also be in the music, and when it's in the music it can be ambiguous and when it's ambiguous, its meaning is limited only by the mind of the listener. It's difficult to overemphasise the magic of this point.

Take the heavy drum rhythm from Queen's 'We will rock you.' What do think it means ? Have a few moments to think about this or any other strong rhythmic intro you're familiar with. In reality a strong rhythm 'means' absolutely nothing but psychologically, any human being is going to react to it because it stimulates primitive parts of the brain. It's predictable, reliable, determined, even defiant, it symbolises all these and anything else you personally can think of.

In 'We Will Rock You,' the drums are also a metaphor for the song because they hook you from bar one and continue right the way through to last. They are the spine of the song but more than that. They are also symbolic of Queen the band. They are going to 'Rock You.' And they reaffirm this in both refrain and title.

So that drum beat is a top draw metaphor, as is the motif in Beethoven's fifth symphony, or the off beat rhythm in Kylie Minogue's, 'Can't Get You Out of My Head.'

All these bits of song 'mean' something quite profound. Something other than themselves which can't be put into words. This is what makes the language of song so unique and powerful.

19. Message : Important

Were it not for a few subtle psychological song quirks; I'd have labelled the message 'essential.' The first is that the message you put out into the ether is only half of it. The other half is what the listener brings with them. Individual life experience will be unique and they will have subtle variations in how they interpret what you're saying and how they feel about it. As no two people are the same, you'll have a hundred interpretations for every hundred listeners. This quality is what makes art such a precious personal and cultural gem.

Were it not for a few subtle psychological song quirks; I'd have labelled the message 'essential.' The first is that the message you put out into the ether is only half of it. The other half is what the listener brings with them. Individual life experience will be unique and they will have subtle variations in how they interpret what you're saying and how they feel about it. As no two people are the same, you'll have a hundred interpretations for every hundred listeners. This quality is what makes art such a precious personal and cultural gem.

Secondly, you can have a song where the message is uncertain or obscure or just plain missing. There will always be songs where audiences get hooked without it having a specific message because sometimes it just feels right.

You see, what our brain needs to hear is not always in the logic. It may be a complex, subtle or aggressive combination of sounds which stimulate chemical releases that we find soothing or uplifting. The message or meaning is not the primary hook, it's deeper, and we don't necessarily need to know what it is in order to to understand and empathize with it.

Luckily, the complexity in music matches the complexity of our minds. There is a multi faceted healing property which resonates with our humanity at very primal level. You already learned as child, at times when there's a need to express our basic emotions, a certain amount of whining pitch variation is enough to get the message across.

Lastly, we humans often lack the ability to say what we mean and mean what we say. This actually is not such a bad thing because, like it or not, our brains prefer to listen to a great big long story from which we can take pleasure in making our own interpretations and deciding how we feel about it.

So you see, the message and the meaning, are just as much part of the listener's heart and mind as the writer's.

20. Character : Essential

Songs must feature a protagonist with something to shout about. It could be an optimistic announcement which heralds greatness, or a gloomy rant about the end of the world. It doesn't matter which. What matters is that singer cares about it enough that they want their feelings heard. The next four headings are all elements of character.

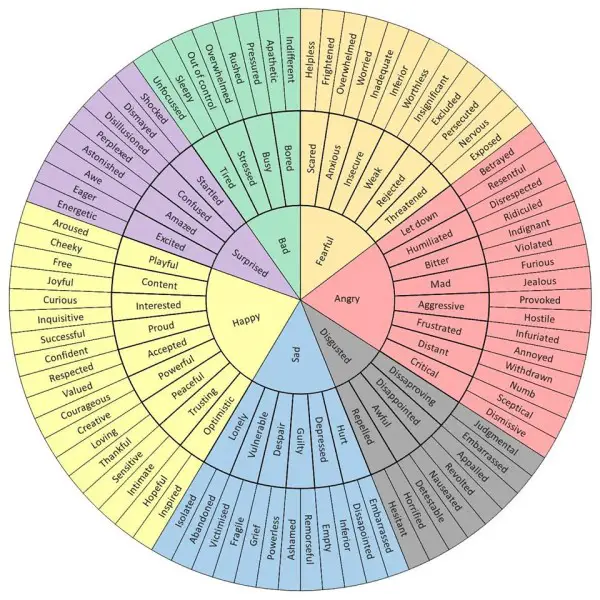

21. Emotion : Essential

Image courtesy of Onesimusix

Image courtesy of Onesimusix

You will struggle to find a piece of music from any part of the world which doesn't express or illicit emotion. That's what music is, the sound of emotion.

Many people have difficulty finding the right word to express emotions. Young adults are often overwhelmed by conflicting emotions which explains why music can be become so important to them. Also, there a conditions such as alexithymia which limit individuals' emotional awareness. Again, music can act as an interpreter.

A really useful tool for song writing or anyone wanting a better understanding of emotions is a 'Feel Wheel' or 'Wheel of Emotion.' There are many charts similar to this one and a quick search may find one which suits you better. If you're serious about song or getting to understand emotions, I encourage you to download the image. The original idea comes from psychologist, Robert Plutchik. Read about him here. This version is credited to 'Onesimusix' https://imgur.com/tCWChf6

When you begin to write a song, you should get your head around the emotions involved and build a story around them. Your listener will do the rest.

22. Attitude : Essential

When skilfully crafted, song surpasses any verbal message and expresses our humanity in a way that no other art form is capable of. The conflict or joy is not only portrayed, but the resulting chemical changes should also experienced by the listener.

This chemical communication is what song writers seek and is the reason for the song's existence. To achieve this level of exchange, their needs to be an almighty dose of attitude. In particular, attitude toward the emotions being expressed.

Unfortunately, it's not enough for the protagonist to be angry about his unreasonable boss. He needs to be angry about the fact that his boss made him angry. That's where the song is – and it's the same with a dance song. The lover might be upbeat and happy because she's meeting her fiancé for a night of dancing. But she needs to be delirious because only he can make her feel like this, anyone else won't do - dancing with him is the only thing she wants to do. And, you guessed, she's deliriously happy about being deliriously happy. I'll run the risk of labouring the point with third example because it's so vitally important.

Take the children afraid of the dark, they must not only be afraid of the dark, but be afraid of the fear. So in all three cases there is a second phase to the emotion. An almost a fanatical attitude to the initial emotion being expressed. An uncompromising polarity which may appear slightly insane but none-the-less, is both appealing and believable because that's what happens in real life.

The protagonist with attitude, is one of the most important elements of a song and you ignore this one at your peril. If a songwriter doesn't give characters believable hang ups, the song is doomed. If the performer lacks the personality to translate the weirdness of being emotional, the song is doomed.

23. Vulnerability : Important

Image courtesy of Mubariz Mehdizadeh

Image courtesy of Mubariz Mehdizadeh

Talking of hang ups; in a song, even happy characters will usually show their weaknesses. They also demonstrate a certain amount of shame or embarrassment in relation to those weaknesses. They are at the mercy of them and they're very often torn between their vulnerability and coming to their senses.

These are age old dilemmas which we all face at some point in our lives. Analyse any song and eventually you'll uncover a situation where the world is not fair and the singer is being undone by it.

There also songs where characters demonstrate untouchable resilience. Rap, rock and religious music are prime examples where fortitude may feature quite heavily. But scratch beneath the surface and what do we find ? Oh yes, the need to express strength is often born out of vulnerability and the song which helps bolster confidence and put aside fears is merely a front, a false facade which serves to protect a soft underbelly and turn fear into bravado. Song is very good at this.

However you use it, vulnerability is the key to getting listeners to explore their own empathy. Allow them to feel the singer's pain and it unites, singer, song and audience in a very personal manner.

24. Empathy : Important

Empathy is the chain which binds the listener to the character. Just as the character cares about their dilemma, so too the listener must have empathy for them.

There are several ways to go with empathy. You could invite the listener to feel empathy for the singer with first person narrative, such as, 'I'm so blue – my baby left me.' OR you could transfer it to a third person, in the manner of 'Jenny was down again, Johnny let her down again.' OR you could allow the listener to assume control of the song and bestow your empathy upon them through your wise words. For example, 'I'm gonna stand big and tall, I might stumble I might fall,,, etc.'

What ever type of song you make, it's unlikely you'll have empathy uppermost in your mind. You'll probably just stumble into it because you have a great story to tell about Jenny. That's fine and normal, as long as you're aware that it's always there in some form. What is important is that you recognise opportunities to encourage empathy with an audience because it builds trust through a shared experience.

25. Context : can be Optional, Important, Essential

Context is the circumstances in which the song will be heard. Imagine you're asked to write ten songs for a musical. You wouldn't want all your ten songs to be of the same genre with the same tempo and instrumentation. Nor could each song be a broken hearted love ballad. It would make for a very dull and repetitive experience. You would probably write the opening and closing songs to be upbeat to leave you audience with a sense that, even though there was sadness, it all worked out in the end.

Other contexts might be a live concert or an album or artists debut single. What sort of song would best suit these circumstances ? And how does the context suddenly dictate some of the musical elements discussed in this chapter ? It doesn't take long before you realise that context can actually help make some decisions for you, especially as you become more experienced and begin to work on larger projects.

A good rule of thumb is to adopt a 'Big Picture – Little Picture' mindset. The current song must always deal with the issues in front of the singer. This is the Little Picture. But you, as the writer must be consciences of how it fits with other material which goes before and after. That's the Big Picture.

For centuries, operatic composers used a mixture of big choral anthems followed by instrumental followed by ballad or recitative ( a type of talk-song ). It's a good idea to follow there example and mix things up or an audience will get bored.

Considering context will come naturally as you write more, you should definitely not ignore it.

Brief Summary

Image courtesy of Jason Rosewell

Image courtesy of Jason Rosewell

Every song does not need every element, that would be overkill and you'd probably end up with a dog's breakfast. To get started, you only need a rhythm, a melody and something to shout about. Everything else will come naturally if it's needed at all. Check out my table, print it out and stick it on your wall. Good luck.

| 25 special songwriting secrets | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Essential | Important | Optional | |

| 1 | Writer's Mind | ||

| 2 | Listener's Mind | ||

| 3 | Story | ||

| 4 | Words | ||

| 5 | Rhyme | ||

| 6 | Repetition | ||

| 7 | Melody | ||

| 8 | Rhythm | ||

| 9 | Tempo | ||

| 10 | Volume/Dynamic | ||

| 11 | Harmony * | Harmony * | Harmony * |

| 12 | Instrumentation | ||

| 13 | Genre | ||

| 14 | Performance | ||

| 15 | Crescendo * | Crescendo * | Crescendo * |

| 16 | Structure/Form | ||

| 17 | Hooks * | Hooks * | Hooks * |

| 18 | Metaphor | ||

| 19 | Message | ||

| 20 | Character | ||

| 21 | Emotion | ||

| 22 | Attitude | ||

| 23 | Vulnerability | ||

| 24 | Empathy | ||

| 25 | Context * | Context * | Context * |

* Importance may vary from 'Essential' to 'Optional.'